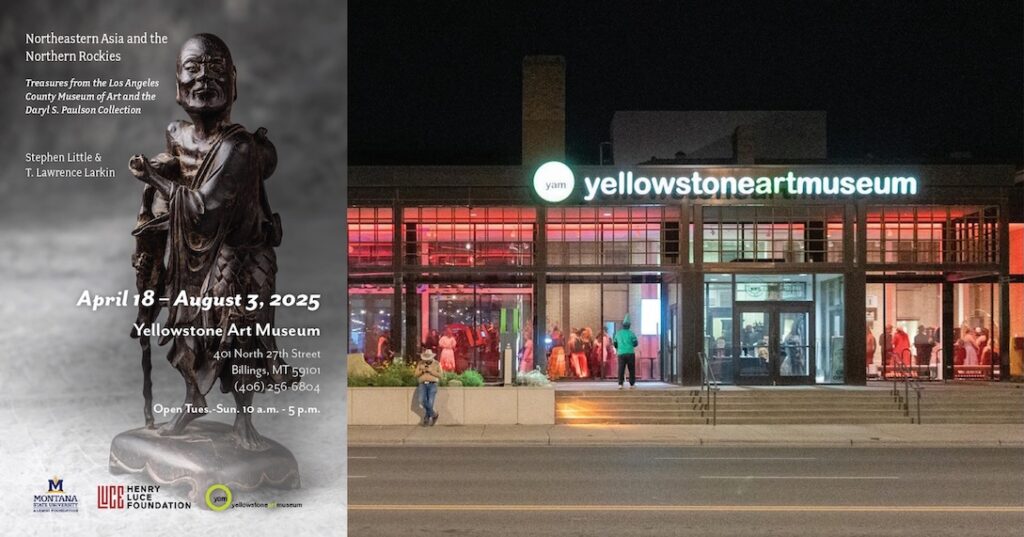

With the support of an Asia Program Grant from the Henry Luce Foundation, Curator Stephen Little and Professor Todd Larkin co-curated an exhibition of religious or ritual objects from the collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Daryl S. Paulson Collection at the Yellowstone Art Museum, Billings, from 18 April to 3 August 2025. Little and Larkin wrote all of the wall text and labels for the galleries, together with a comprehensive catalog available through Punctum Press. What follows are Larkin’s texts for the greater show and for the thematic gallery on Asian migrant art and ritual.

Northeastern Asia and the Northern Rockies: Treasures from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Daryl S. Paulson Collection

As the republic of the United States expanded westward over indigenous lands in the mid- to late nineteenth century, the annexed territories became widely known as places of opportunity for those in search of plentiful work, affordable lodging, and community development. Peoples of European and Asian origin inevitably converged on the Inner West and tensions emerged over access to opportunities within the burgeoning mining, transport, and service economies. While scholars have long concentrated on legal barriers, employment disparities, and social segregation in the West, this exhibition seeks to consider the artistic and cultural traditions that were important centering mechanisms for migrant communities throughout Idaho, Montana. Wyoming, and Colorado, and continue to resonate today.

Northeastern Asia and the Northern Rockies offers an introduction to the “three foundational philosophies” of Asia—Confucianism, Daoism (and to a lesser extent to Shinto), and Buddhism—as represented through a selection of fine art objects. These objects aim to help visitors understand key elements of both traditional and modified forms of these philosophies important to native and migrant artistic and cultural expression. Chinese, Japanese, and Korean migrants succeeded in projecting their ideas and aesthetics onto these Western geographies and adapting the resources they found there, thereby preserving their moral values, affirming their identities, and contributing to life in the West.

The roots of the three philosophies in Northeastern Asia are represented with objects dating as far back as the 5th century BCE, followed by local manifestations as they were adapted to the Mountain West between 1850 and 1918. The first part contains three evocative object groups central to understanding the concepts of Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism, underpinning traditional Chinese culture and much of later Japanese and Korean culture. The second part juxtaposes religious artifacts and historic photographs to evoke the various ways Northeast Asian migrants and settlers adapted the philosophies to daily life and seasonal ritual. The third part incorporates a selection of works by contemporary Asian American artists to encourage a broader conversation about the cultural richness and continued acculturation experienced across the Rocky Mountain region. Through these artists’ personal reflections—on familial relationships, heritage, history, and spiritualism—a universal lesson is revealed: everyone living in this land carries a multifaceted identity.

This exhibition of art from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Daryl S. Paulson Collection, the state archives of Idaho, Montana, and Colorado, studios of regional artists, is made possible in part by an Asia Program Grant from the Henry Luce Foundation, committed to fostering new research on northeast Asian art and culture and reaching out to citizens of the American West to reconnect with their history and traditions.

“Trans-Pacific Transmissions” section of the exhibition, Upper Gallery, Yellowstone Art Museum, Billings.

Trans-Pacific Transmissions: The Adaptation of the Three Philosophies to the Northern Rockies, ca. 1850-1918

This gallery elucidates how Chinese and Japanese migrant and settler visual culture of the Northern Rockies in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries manifested Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. The transmission of the three philosophies from the rural districts of Guangdong province in southeastern China and Kyushu and Honshu islands of southern Japan to the bustling mountain towns of Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and Colorado resulted in an improvised yet vibrant philosophical culture and ritual.

In conformity with Confucius’ teachings, the family was the basic unit of East Asian society: the patriarch served as a moral exemplar, honoring the elders and ancestors, modeling correct behavior, mentoring his eldest son, and guiding the other children to fulfill supporting roles and obligations. However, this order could be severely tested when resources, whether land, income, or food, were in short supply. The dire economic conditions of the southern Chinese and Japanese provinces compelled many bachelor sons who resided there to become “sojourners”—that is, those who seek work and investment opportunities abroad in the short term, sending money back home in a gesture of filial piety, and deferring the responsibilities of marriage, child rearing, and elder care until much later.

The men who braved the rugged and inhospitable terrain of the Northern Rockies were largely employed in mineral mining, railroad construction or rail transport, vegetable or grain farming, and retail sales. A tribute to their capacity for order and organization, they established town districts and regional support networks underpinned by family associations (kongsi), merchant guilds or regional social clubs (huiguans), and Daoist folk deity temples (gongs) intended to offer shelter or sanctuary, provide employment contacts, encourage solidarity, settle disputes, and punish wrongdoers without recourse to American authorities. These organizations also encouraged migrants to moderate conduct in the form of inscriptions and images. A sojourner who became betrothed to a local woman or arranged for his “picture bride” to join him in the mountain community gained a partner in his labors and in the raising of children, the wife adopting a domestic role in the home and the eldest son serving as teacher of the younger siblings.

Chinese and Japanese sojourners followed different popular religions: whereas the former adapted traditional Daoist rituals with an emphasis on folk deities Guan Yu, Suijing Bo, or Beuk Aie, the latter adapted traditional Buddhist iconography with an emphasis on Amida of the Pure Land Paradise. Furthermore, they tended to honor their deities differently: the Chinese formed associations, built communal temples, and made ritual displays in public; the Japanese installed small shrines in their homes and conducted rituals in private; and the Koreans pursued native cults or sought out local Methodist chapters. For this reason, there is far more material and photographic evidence of Chinese ritual than of Japanese or Korean ritual in the state historical society museums and archives of Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. The small but vivid selection of artifacts displayed here are meant to evoke the religious observances of the Chinese who erected temples in mountain towns as well as those of the Japanese who established homes in the fertile valleys, with a final tribute to the Chinese New Year parade which became a highly anticipated attraction for all residents.

Interior of Joss House, Virginia City (Montana), ca. 1875-1900. Photograph. Idaho Historical Society Archives, Boise.

Gong (Deity Temple or Joss House) and Altar Niche

When a Chinese community in the Northern Rockies reached a few hundred residents, the members acquired the financial and material resources to raise and maintain a gong (deity temple or “joss house”) on the town’s main street or adjacent thoroughfare. Although the early log or mature timber truss-and-clapboard structure of the western American mining town was less impressive than the interlocking post, lintel, and bracket structure of southeastern China and southern Japan, it served as an important space for the deity image, sacred objects, and daily rituals within.

Scholar Philip Williams has observed that the Chinese temple built at the eastern end of Wallace Street in Virginia City in the 1860s was originally a single-story log building, but that the community grew in population so rapidly that a second story was added by 1885, permitting meetings to be held downstairs and services upstairs. On the exterior, the door was flanked with red boards inscribed with calligraphic greetings. On the interior, an elaborately carved console supported a niche bearing a painted image of a militant deity (Guan Yu, God of War and Brotherhood, or Zhenwu, the Perfected Warrior), the whole accentuated with embroidered banners, and silk curtains. Before the deity was placed burners, votives, and bells to honor the god, to call him to witness, or to implore aid. The suppliant who wished to make an offering approached an intervening table laden with cups and bowls and incense sticks; one’s fortune could be determined by extracting one of a cluster of numbered straws from a can and matching it to coded phrases in the I Ching (Book of Changes) or putting forth a question and tossing a few augury planks on the floor to determine a response from their disposition. The temple served as a place to congregate for religious and civic purposes, not only to offer messages or libations to the gods, pray to the ancestors, and practice divination, but also to exchange news, offer arbitration, and hold meetings.

Although no components of the deity temple of Virginia City survive, a few sacred objects from the Guan Yu shrine of Helena, first a modest single-story log cabin located at 206 Clore Street (now Park Avenue) around 1880 and later a large timber truss building on Main Street in the 1890s, have been preserved. The altar niche is a remarkable example of Chinese woodworking to honor Guan Yu. The image of the deity has sadly been lost; however, the shallowness of the niche suggests that it once contained a figural painting or low relief, creating an effect not unlike that at the Virginia City temple. The highest lintel features delicate carvings of flowers alternately coupled with birds (day) and bats and moths (night); a green ribbon bearing the name of Guan Yu appears to descend to the jambs to proclaim his chief virtues: resolve, loyalty, courage, and justice. An openwork canopy incorporates paired fish converging on water plants, perhaps evoking the diet of migrants from the Pearl River Delta of Guangdong Province.

Statue of Guan Yu from Butte, ca. 1905. Montana Heritage Commission, Virginia City. Altar Superstructure (Niche) dedicated to Guan Yu, ca. 1890. Montana Historical Society Collections.

Guan Yu

The name of Guan Yu (or Guan Di), a warrior of the late Han Dynasty who was revered as a guardian deity exemplifying the qualities of bravery, loyalty, and brotherhood during the Sui Dynasty, was the most prevalent deity in temples and shrines throughout the Northern Rockies, found in gongs (deity temples) and tongs (masonic lodges) alike, which can be explained by the necessity of men who banded together for mutual protection or benefit and who upheld the strongest standards of ethical conduct far from home selecting a guardian figure and role model. The Chinese migrants of Butte, Montana, celebrated Guan Yu’s birthday every 22 June by decorating the temple, flying the Chinese flag, playing music, and lighting firecrackers. Part of a new shrine the Butte’s Chinese migrant community imported from China around 1905, the Guan Yu statue featured here has a high golden cap and crown, long reddish face, exaggeratedly slanted (“phoenix”) eyes, thin pursed lips, and tripartite beard falling freely over a lavish green robe integrating blue, red, and gold zoomorphic designs and tied with a double belt. With one hand raised to the heart and the other resting on the knee, he seems to be invoking the faithful to show inner strength and calm. Carved of a single piece of wood, the body has cracked doubtless due to the dry climate of Western Montana. As impressive as the statue is, it was originally placed within a freestanding wooden superstructure articulated with a precision machine-cut arched proscenium flanked by vases bearing sacred bouquets (jinhua) and flowering trees bearing scrolls inscribed “Happy New Year” and “May you have good fortune” in conformity with older folk Daoist spiritual fare in Guangdong Province. An assortment of pots and burners filled with sand served as a support for candles and incense sticks. The table was set with three porcelain dishes, chopsticks, and a pouring vessel for offerings.

Altar Cloth (right), 1890s. Idaho State Museum, Boise. Upper Gallery, Yellowstone Art Museum

Altar Cloth

Next to the sawn niche and the carved deity, the embroidered cloth was significant in designating the altar as a protected space for leaving offerings for the gods and ancestor spirits. Although historic photographs suggest that most high altars and subsidiary supports in the Inner West were simple four-legged tables with rectangular plank tops and lathe-turned legs, the embroidered cloths that covered some or all the support were usually imported and featured a variety of designs. For example, cranes at the Lewiston temple represented wisdom, longevity, and immortality and fish at the Evanston temple signified wealth, luck, and prosperity. Here we see Shishi (Foo Dogs or Guardian Lions), articulated with green glass eyes and gold, blue, pink and orange bodies, which stand for protection, power, and good fortune. This green silk altar covering with a bright pink and blue floral border is likely from a deity temple or masonic lodge in Boise.

Butsudan (Amida Buddha in Meditation), 16th century. Carved, gilded, and lacquered wood, 11 ½ x 5 x 4 ½ in. Gift of Sennosuke Ogata, Richard E. Peeler Art Center, DePauw University, Greencastle.

Butsudan and Amida

A Japanese migrant who worked the rails or settled on a farm in the Northern Rockies usually carried with him a devotional inscription, illustration, or statue of Buddha and installed it in his room at the boarding house or a communal room of the family homestead. Buddhist shrines were very common in the houses, towns, and along the roads of Southern Japan, where individuals, families, and monks directed prayers to Buddha represented by a figurine on a low plinth or encased in a tall Butsudan (lit. Buddhist altar, or free-standing cabinet with a series of doors and screens opening on a central niche bearing the Buddha and a range of subsidiary compartments for talismans, offerings, portraits, and mementoes) and made devotions to deceased family members. The sojourner was usually contented with a small, portable shrine consisting of a simple niche-with-doors enclosing a statue or inscription signifying Buddha. Eric Walz has surmised that such Butsudans were found in about half the Japanese American dwellings of the Inner West.

The most popular Buddha of the Edo period was Amida (or Amitabha) of Pure Land Buddhism, who as a monk vowed that any being who desired to be reborn into his Western Pure Land should repeatedly invoke his name. The dominant sect of Pure Land Buddhism in the Northern Rockies in the 1890s was the Jodo Shinsu group, who advocated appealing to the infinite wisdom and compassion of Amida. Professionally crafted late nineteenth-century Butsudans possess a cylindrical case, lacquered black on the exterior, with paired doors that open to reveal an exquisitely carved and gilded Amida, seated in an attitude of meditation, wisdom, or compassion supported on a multi-layered lotus plinth and backed by a flaming mandorla. Individuals could approach the small shrine at any time, clear the mind of all worldly concerns, bow heads in reverence, and chant the name several times. The sixteenth-century giltwood statue of Amida Buddha in Meditation shown here was passed down in the Ogata family for more than three hundred years—until Sennosuke Ogata converted to Christianity in 1873, studied at DePauw University from 1885, and became a Methodist missionary in the Tokyo area. Although the object has a rich history within the Ogata family and Japanese study abroad programs of the last quarter of the nineteenth century, it evokes the many portable Butsudans Japanese migrants and immigrants brought with them to the American West or replicated with imported or local materials for use in the home. George Hirahara’s photo of the Yumibe family gathered around a Butsudan in their quarters at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center suggests that it continued to serve an important function in affirming faith and identity during World War II.

Chinese Banquet Suit, ca. 1900, and Parade Standard, ca. 1905. Idaho State Museum, Boise. Upper Gallery, Yellowstone Art Museum

Ceremonial Suit, Standard, and Dragons

Lunar New Year, a festival occurring between late January and mid-February to bid farewell to the old moon and to welcome the new one, was most valued by Chinese migrants and immigrants of the Inner West, not only because it reminded them of the old world and provided an occasion for a reunion of living and dead souls but also because it served as a reminder of personal responsibilities to be met and social hospitality to be extended in order to ensure harmony in the individual and the community. The Chinese cleaned lodgings and businesses, paid outstanding debts, washed their bodies, donned fine clothes, offered gifts to clients, gave lichee nuts and candied fruit to children, and hosted parades, games, and banquets.

The New Year’s parade was a standard spectacle of every city with a sizable Chinese population, from Boise to Denver. In Boise, for example, the day began with a solemn rite performed at the Suijing Bo Temple on the corner of Seventh Street and Idaho Street, where the faithful honored the memory of the great warrior and gave thanks for blessings received in the previous year. A procession then formed comprised of a line of men on foot, two with a gong, cymbals, or drum, two holding Chinese Empire and United States flags, six in white changshans (or long formal gowns) bearing standards, a few carrying richly embroidered temple banners, and a half dozen or so shouldering a green and yellow long (or dragon) comprised of a snarling papier-maché head and long scaley membrane, a series of carriages bearing women in traditional garb trailing behind. The young men animated the dragon, a symbol of power, strength, health, benevolence, and good fortune, by bowing before the temple and then swaying the head and winding the body down Seventh Street until they covered the length of Chinatown and then turned on to Main Street. This procession was accompanied by a band of flutes, clarinets, strings, and drums, dancers waving streamers, and residents throwing firecrackers. After the parade, the Chinese returned to their homes and refreshed themselves for afternoon visits with neighbors and games before the temple, followed by evening feasts and revelry, a party that went on for days.

Although few of the objects employed in Chinese parades have survived due to their delicate materials or continuous use since the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries, the Idaho State Historical Society has preserved a man’s lavender tunic and chartreuse vest imported from the Guangdong region around 1903 and a standard carved, painted, and gilded with a floral and leaf design centering on a glass window around 1910, both of which are displayed here. A period photograph from the University of Wyoming provides a sense of the craftsmanship that went into shaping the dragon’s immense head, complete with bulging eyes, snarling nostrils, protruding horns and whiskers, and the extraordinary coordination of twenty men as they maneuvered the scaley body through the streets of the sister cities of Evanston and Rocky Springs in 1899. The contemporary parade dragon imported from China included here, though realized in more modest design and ephemeral materials, conveys the spirit of revelry with which the Chinese continue to greet the Lunar New Year.